Beyond ‘Just Try Harder’: The Real Science of Why Work Feels Hard

Ever wonder why some challenging tasks feel rewarding while others just drain you? Or why your colleague eagerly volunteers for projects you’d avoid at all costs? The answer lies in our complex relationship with effort and how it shapes our motivation.

Why Do Some People Love Hard Work While Others Avoid It?

We’ve all experienced it: watching someone enthusiastically tackle a difficult task that we’d personally avoid. This is how I feel when someone asks me to build spreadsheets. This type of feeling, though, is important to notice and recognize in ourselves.

It’s even more important to create an environment where we make it safe for those around us to lean into this as well. You may be familiar with the trend of skills based work models but here, we believe that cognitively inclusive work environments (supporting neurodivergence) will be based in aligning interests and motivation based work.

Working with my technical founder, we’ve realized the importance in this as we build. What motivates us and drives our effort is different. For example, I’m energized by creating tangible impact and seeing our solutions make a difference for users—the effort feels worthwhile when I can measure its effect. I favor doing tasks where I can see the impact. Meanwhile, my cofounder is driven by technical challenges themselves—he enjoys the process of solving complex problems and trying new innovative approaches even if their impact isn’t as immediately tangible.

This isn’t wrong—they’re just different motivation profiles that reveal how effort affects each of us differently. In fact, each approach brings a special value to how we balance the work and how we prioritize features and the technology stack.

But this doesn’t just go into what motivates us to do our work, it impacts how we perceive the work itself. I could have work that results in a huge impact but find that the effort required is too high.

How Does Effort Affect the Value of Work Outcomes?

Recent research by Marcowski, Białaszek, and Winkielman (2025) suggests that effort can have positive, negative, or even non-monotonic effects on how we value outcomes. This groundbreaking study helps explain why some people seek out difficult challenges while others avoid them, and why the same person might find effort rewarding in some contexts but aversive in others.

According to Howard et al. (2021), motivation isn’t one-dimensional. Each of us has a unique profile made up of different motivational drivers:

- Intrinsic motivation: Doing something because it’s inherently enjoyable

- Identified regulation: Doing something because you personally value the outcome

- Introjected regulation: Doing something to avoid guilt or maintain self-worth

- External regulation: Doing something for rewards or to avoid punishment

These researchers identified four distinct motivation profiles in the workplace:

- Highly Self-Determined Profile (22.3% of people in the study): High levels of intrinsic motivation and self-determination

- Identified Profile (28.9%): Driven by personal values and the importance of tasks

- Low Self-Determined Profile (15.7%): Generally low motivation across all types

- Externally Regulated Profile (33%): Motivated primarily by external factors like rewards or obligations

But Marcowski’s research takes this a step further by examining how effort itself also influences our internal systems. Their findings reveal that the relationship between effort and value isn’t fixed—it changes based on:

- Temporal orientation: Whether you’re considering effort before expending it (prospective) or after you’ve already put in the work (retrospective)

- Tangibility: Whether the effort and rewards are real or hypothetical

Most importantly, they found that in real-world settings, greater effort decreased outcome value when considered prospectively (before doing it), but increased outcome value when considered retrospectively (after doing it). This explains the “IKEA effect” (valuing things more when we build them ourselves) and why we sometimes abandon tasks before starting them if they seem too difficult.

How Does ADHD Change Your Relationship with Effort?

For those with ADHD, like myself, effort and motivation work differently due to neurochemical differences that affect how rewards are processed.

In my experience, my motivation is heavily influenced by:

- Effort-Value Calculations That Shift Rapidly: My brain performs complex calculations about whether effort is “worth it,” but these calculations are highly influenced by interest, not just importance. A task that seems worth tremendous effort one day might feel impossible the next if my interest wanes.

- Non-Linear Effort-Value Relationships: For me, small efforts often yield little motivational value, medium efforts can suddenly become highly rewarding, but very high efforts can trigger avoidance—creating exactly the non-monotonic patterns identified in Marcowski’s research.

- Temporal Effects on Steroids: The prospective/retrospective divide is even stronger with ADHD. Looking ahead at effort can often feel overwhelming and even devalue the outcome, but looking back at completed effortful tasks brings enormous satisfaction.

When Effort Overwhelms ADHD

Particularly for me, I experience a lot of “out of sight, out of mind.” So when I accomplish a task, it often feels as if I did nothing even when I truly accomplished a lot during the day or week. When I’m able to look back at the completed work, though, I have a better ability to appreciate and recognize the value of the work being done.

In transparency, this is also a contributing factor to why I struggle to break down my tasks into smaller detailed tasks. As I do, the effort required increases because of the sheer number of individual steps that lead up to even the simplest of things.

An example of setting Implementation Intentions in stick figure format

This past week, I “tried” to go to the pharmacy three different days and even used Implementation Intentions to set the day and the time. Three times. But then I started to break down the actual steps, and as I realized that parking in the parking garage was hard because of the size of my car, that getting into the pharmacy is a challenge, that the drive is out of the way from my normal route and will increase my commute… I didn’t go. The effort had grown beyond the perceived value and even the perceived “pain” of not going.

Understanding these patterns has transformed how I structure my work.

How Does Autism Influence Effort-Value Relationships?

For autistic individuals, we’ve seen effort and value interact in distinct patterns:

- Predictable Effort-Value Connections: Many autistic people thrive when the relationship between effort and outcome is clear and consistent, reducing the cognitive burden of unpredictable reward structures.For us, we see this work best when we’re able to connect the purpose — not just the outcome as part of the effort. Adding in “why” we do something makes drawing the connections easier, particularly as it’s easy to find that outcomes do not always naturally make sense. This also helps to set clear expectations.

- Effort as Intrinsically Valuable: For some autistic individuals, the systematic application of effort itself can be rewarding, particularly when directed toward special interests—creating a positive relationship between effort and value.This can often lead to hyper-focusing on specific activities and naturally increase the intrinsic value of activities.

- Effort Thresholds: Social efforts may have a high initial cost with little perceived value until a certain threshold is reached, creating a non-linear relationship between social effort and perceived rewards.

These patterns help explain why neurodivergent motivational styles can represent both challenges and strengths, depending on the environment and the nature of required effort.

What Happens When Effort Becomes Valuable Instead of Costly?

The “effort paradox” described by Inzlicht et al. (2018) highlights that effort can be simultaneously costly and valued. Marcowski’s research builds on this by identifying four distinct patterns in how effort affects value:

- Decreasing Profile: Greater effort consistently decreases value (following the classic “law of less work”)

- Increasing Profile: Greater effort consistently increases value (reflecting the “effort as value” hypothesis)

- Decreasing-Increasing Profile: Value initially decreases with effort but then increases after a certain threshold

- Increasing-Decreasing Profile: Value initially increases with effort but then decreases after a certain threshold

These last two non-monotonic patterns are particularly interesting because they show how our relationship with effort can shift at different intensity levels.

For example, I might avoid starting a task requiring moderate effort (decreasing value), but once I’ve invested substantially in it, additional effort actually increases my commitment and perceived value (increasing value).

My technical cofounder, however, often shows an increasing-decreasing profile—he actively seeks challenging tasks and values them more as they get harder, but only up to a point. Once the effort exceeds his optimal challenge level, additional effort starts decreasing his motivation.

How Can You Identify Your Personal Effort-Value Profile?

Understanding your own effort-value relationship can transform your approach to work and life:

1. Observe Your Effort Responses in Different Contexts

Pay attention to how effort affects your motivation in various situations:

- When do you find difficult tasks rewarding?

- When does effort make you avoid tasks?

- Does your relationship with effort change when you’re already invested versus just starting?

2. Identify Your Effort Thresholds

Most of us have points where our relationship with effort changes:

- At what point does effort transition from being motivating to demotivating?

- Are there certain types of effort (physical, mental, social) that have different thresholds?

- Does the presence of others change your effort thresholds?

3. Recognize Temporal Effects

Consider how your perception of effort differs:

- When contemplating future effort (prospective)

- When reflecting on past effort (retrospective)

- When currently engaged in effortful activity (in-the-moment)

How Can Understanding Effort-Value Relationships Transform Your Work?

Once you understand your personal effort-value patterns, you can design your environment accordingly:

For Decreasing Profiles (Effort Reduces Value):

- Structure work to require shorter bursts of effort

- Create clear reward schedules for completing difficult tasks

- Use accountability systems that make avoiding effort more costly than engaging with it

For Increasing Profiles (Effort Enhances Value):

- Seek out appropriately challenging tasks

- Build in opportunities to demonstrate mastery through effort

- Connect your identity to the value of hard work

For Non-Monotonic Profiles:

- Identify your effort “sweet spots” where value is maximized

- Create systems to help you push through effort thresholds. This can look like automating and linking effort to trigger events.

- Use temporal framing to your advantage (e.g., focusing on retrospective value when prospective value is low)

ADHD-Specific Strategies:

- Design environments that reduce friction for starting effortful tasks

- Create immediate rewards for effort expenditure (but know this has limits)

- Use body doubling and accountability to overcome initial effort aversion

- Schedule demanding tasks during periods when your effort-value calculation is most favorable. This can often look like following energy trends and circadian rhythms.

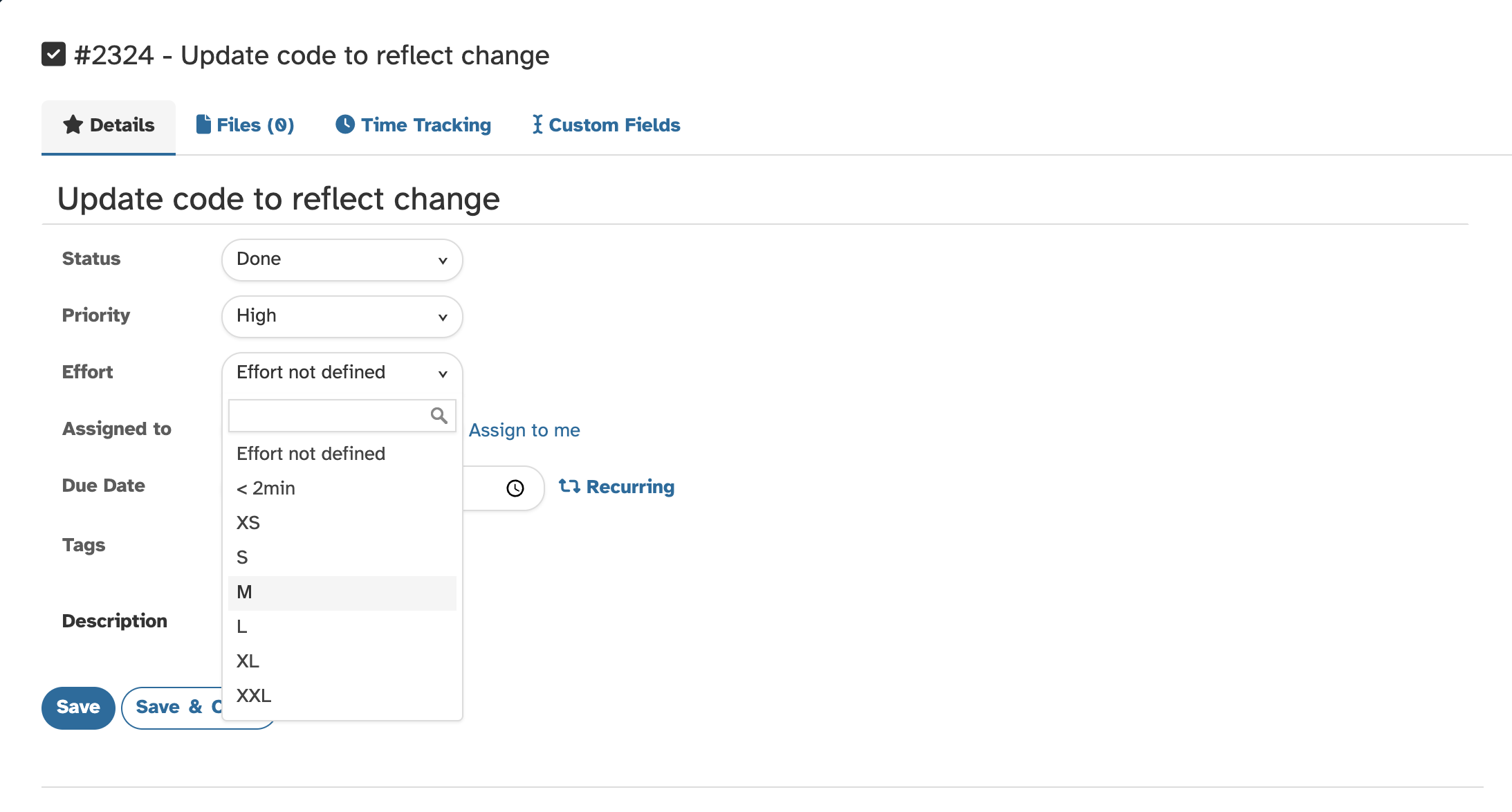

Setting Effort in Leantime is done through T-shirt sizing.

How Do Different Effort-Value Profiles Complement Each Other in Teams?

In teams, diversity in effort-value relationships can be a superpower. At my company, I’ve noticed that having team members with different effort-value profiles creates a more resilient organization:

- My impact-driven motivation helps establish clear outcome metrics

- My cofounder’s enjoyment of effort itself drives technical innovation

- Team members with different effort thresholds excel at different types of challenges

Understanding these differences helps us better inform how we assign tasks and collaborate. Instead of expecting everyone to value effort the same way, we align responsibilities with individual effort-value profiles.

This is also really helpful to recognize as it helps us be empathetic towards our differences and the value (rather than annoyance) that they often bring to the team.

Can You Change Your Effort-Value Relationship?

While research suggests these profiles remain relatively stable, you can influence how effort affects your motivation:

- Adjust your temporal perspective: Try viewing effort retrospectively even when making prospective decisions

- Connect effort to identity: Link effortful tasks to valuable aspects of your self-concept

- Create tangible effort representations: Make effort visible and measurable to increase its perceived value

- Establish effort-reward consistency: Build reliable connections between effort and outcomes

The goal isn’t to fundamentally change your profile but to work with it more effectively while expanding your effort tolerance. These are also fundamentals that we’re building into Leantime as part of our focus on supporting the productivity workflows of neurodivergent minds.

How to Apply These Insights Starting Today

Understanding effort-value relationships isn’t just academic—it’s practical. Here are three steps you can take immediately:

- Map your effort landscape: Note activities where greater effort increases value and where it decreases value

- Experiment with temporal framing: Try making decisions about effort by imagining how you’ll feel afterward

- Design your effort sweet spots: Structure tasks to hit your optimal effort level where value is maximized. We call this the Golidlocks method.

Ultimately, though, please remember that there’s no “right” effort-value profile—just different ways of experiencing the world. The key is understanding your unique pattern and designing your environment to work with, rather than against, your natural tendencies.

By honoring these differences in ourselves and others, we can create work and life structures that allow everyone to thrive.

This article was inspired by research from Marcowski, Białaszek, and Winkielman (2025) on effort-value relationships and Howard et al. (2021) on motivation profiles in the workplace, alongside both personal experience as a neurodivergent founder navigating the startup landscape and as part of my PhD studies in Industrial & Organizational Psychology.

Other articles you may be interested in:

It’s Not Procrastination: Your Work May Be Lacking Inspiration

Boost Your Concentration: Factors that Impact Focus and How to Improve it

Why Do Projects Fail? How to Avoid Failure and Ensure Success