Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

Max Wertheimer is often attributed as one of the primary founders of gestalt theory — with his book on gestalt concepts, “Productive Thinking“. The above, written approximately 20 years before the book was published, explains the premise of the gestalt movement and the idea that: Human beings perceive the world as a whole before seeing the individual parts.

His quote goes a step farther and explains that there are some things that cannot be explained by their individual parts. They can only be explained by the nature of the whole.

There are entities where the behavior of the whole cannot be derived from its individual elements nor from the way these elements fit together; rather the opposite is true: the properties of any of the parts are determined by the intrinsic laws of the whole.

Max Wertheimer (1925), Lecture at the KANT Society on 17 December, 1924.

These principles, while uncommon in traditional Business studies, are fundamental to the human perception of the world — and thus to the way we perceive work and the things around us. Wertheimer also believed that the theory explained what other theories lacked; that is, accounting for how people understand the world around them and how they obtain insight.

In this article, we’ll discuss the gestalt theory and explain its relevance to business, productivity, motivation and how it influences what we do here at Leantime.

Table of contents

- What Does Gestalt Mean?

- What is Gestalt Psychology?

- Who is the founder of Gestalt Psychology?

- How was the Gestalt Approach Formed?

- Psychology: Gestalt Principles

- Gestalt In the Workplace

- Gestalt Psychology in Motivation & Productivity

- What do Gestalt psychology principles have to do with Leantime?

- Leantime exists to connect work + purpose together

- In Summary: Running a business requires more than task management

What Does Gestalt Mean?

Gestalt, a German term often thought to be translated as “whole” or “form,” refers to a psychological and philosophical concept that emphasizes the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

With my cofounder, Marcel, being a German immigrant — I took the opportunity to ask him to translate the meaning of the word and to discuss he familiarity with it. He described a word that he said doesn’t easily translate to English and even “whole” or “form” is not quite right. He described a concept that is almost unreal, “perceiving beyond what you actually see.”

What is Gestalt Psychology?

The realm of Gestalt psychology seeks to explore how our minds perceive and organize sensory information. It studies how our minds emphasize the importance of patterns, context, and the integration of individual elements; pulling them together in order to create meaningful experiences.

This theory highlights that our brains naturally seek to organize fragmented information into coherent, holistic perceptions, which can lead to insights into human cognition, problem-solving, and the understanding of complex phenomena.

More simply, Gestalt psychology is like looking at the bigger picture instead of just the puzzle pieces. We’re seeing the end picture and not realizing it’s made up of individual pictures. It’s a fancy way of saying that our minds don’t just see things as a bunch of separate bits but as a whole, like when you see a face in a crowd instead of just individual eyes, nose, and mouth.

This also means that when we’re looking at the world, we try to find the “most sense” that we can make out of situations. Without diving deep into things like ego and consciousness, it’s this sense (even need) for wholeness that can contribute to cognitive dissonance and the resistance to change.

In psychology, gestalt is a theory that suggests human beings are always in search of order in their mind. This stems from “cognitive dissonance,” or the idea that the human mind cannot hold two conflicting beliefs at the same time. People feel out of order when the beliefs in their mind don’t match.

– Greg Cochlan, “Gestalt: To Gestalt or Not to Gestalt, That is the Question”

Beyond experimental psychology, the concept of gestalt has also found application in various fields, including art, design, and therapy, where it underscores the significance of how elements are structured and how the whole can impact our perceptions and interpretations.

Who is the founder of Gestalt Psychology?

Gestalt psychology doesn’t have a single founder, but it emerged as a distinct psychological school of thought in the early 20th century through the collective efforts of several key figures. Max Wertheimer is often credited as one of the founding figures, as he conducted groundbreaking research on perceptual phenomena, particularly in his famous studies on apparent motion; which played a pivotal role in the development of Gestalt psychology.

Other prominent psychologists associated with the Gestalt psychology movement include Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka. Together, these scholars and their colleagues contributed to the formulation and promotion of Gestalt psychology’s principles and ideas and the emphasis on the holistic nature of human perception and cognition.

How was the Gestalt Approach Formed?

Gestalt has several philosophical influences, including Kant’s epistemology and Husserls’ phenomenological method. Both Husserl and Kant aimed at understanding the human consciousness and the perceived worldview and argued that these mental processes do not involve rational thought.

Similar Gestalt research has found that the brain organizes visual data using the use of groups of information. Gestalt psychology suggests these “shortcuts” make it possible for a person to see something more completely and more quickly.

Psychology: Gestalt Principles

As already mentioned, gestalt psychology is characterized by several key principles that focus on how our minds perceive and make sense of the world. These basic principles have been used in multiple facets of theory now. Here are some of the fundamental principles and patterns of Gestalt psychology:

The Principle of Closure:

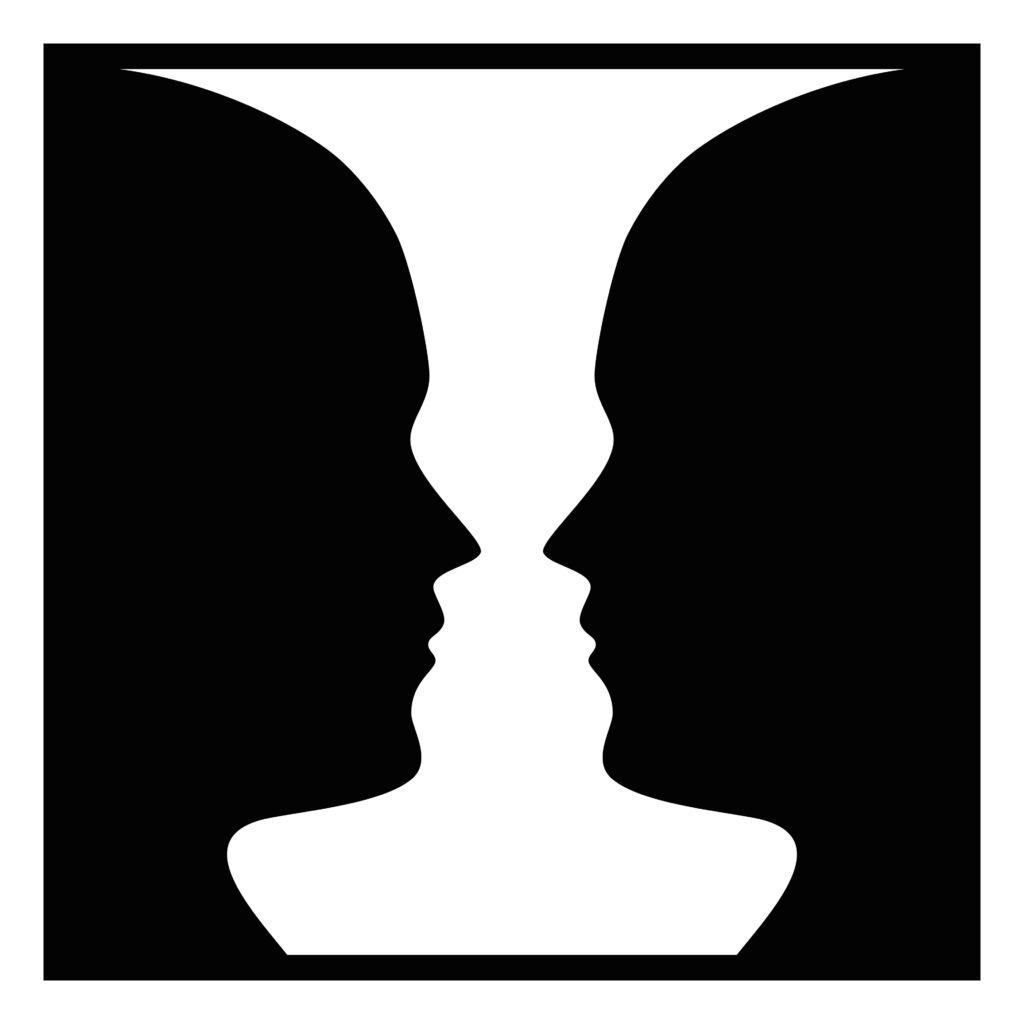

This principle suggests that our brains tend to complete incomplete or fragmented information to perceive it as a whole. For example, we might mentally “fill in the gaps” in a partially drawn circle to see it as a complete circle. In the image below, your mind closes the image to either see an elephant or two faces.

The Principle of Proximity:

This principle states that objects or elements that are close to each other in space are perceived as a group or related, even if they are dissimilar in other ways. When you see a row of dots, for instance, you’re likely to perceive them as a single line rather than individual dots.

The Principle of Similarity:

Objects that share similar characteristics, such as color, shape, or size, are often grouped together in our perception. For example, you might group red squares and blue circles together based on their shared color, even if they are scattered randomly.

The Principle of Continuity:

This principle suggests that our minds prefer to perceive continuous, smooth patterns rather than abrupt changes or disruptions. When you see a wavy line intersected by a straight line, you’re likely to perceive the wavy line as continuous through the straight line, rather than as separate segments.

The Principle of Figure-Ground:

Our perception naturally distinguishes between the main object of focus (the “figure”) and its background (the “ground”). This helps us separate objects from their surroundings, allowing us to focus on what’s important.

The Principle of Symmetry:

Symmetrical objects are often perceived as more pleasing and organized. When confronted with symmetrical shapes or patterns, our minds tend to perceive them as more stable and balanced.

The Principle of Prägnanz (Good Continuation):

This principle posits that our minds tend to organize visual information into the simplest, most stable, and most regular forms possible. When given a choice, we perceive shapes and patterns that require the least cognitive effort.

These principles collectively emphasize the idea that our brains seek to organize sensory information into meaningful and coherent patterns. This highlights the holistic nature of perception and cognition; a concept that is central to Gestalt psychology today.

Gestalt In the Workplace

Psychology is not just for therapists — it is a framework for understanding fundamental human behavior and has application to anything that impacts or interacts with humans. Many times, though, we operate in expertise silos. This means that when we’re in business, we think only in business terms. When we’re in product management, we think in product. When we’re in psychology, we think there.

What we miss here: the crossover in fields. Knowledge and understanding that has so much cross over application that we often forget to look outside of the expected worldview. When we do, though, we open the doors to more learning and a better understanding. This is something really important to us at Leantime.

Project management or work management crosses over into every field. As a result, it needs to be accessible and relatable to us as humans on the way.

So what does gestalt look like in the work place, then?

Gestalt as a Theoretical Design framework: UX focus

One place that you’re most likely to run into Gestalt philosophy is through the art and practice of user design and user experience.

The tendency or ability to group information in order to make sense of it is something that can be easily applied to design. Designers, and even marketers, can apply these principles to help users know how to use a tool, to follow directions or better understand messaging. Or to even get a better recall for the visual elements of a logo.

Designers use these principles to understand how users perceive and interact with digital products and to enhance the overall user experience. Taking a look again at the principles of gestalt psychology mentioned above, we’ll discuss how they are incorporated into the design process.

Proximity and Grouping:

By employing the principle of proximity, designers can group related elements closely together to signify their association. For example, in a navigation menu, placing menu items close to each other helps users recognize their relationship. This enhances the user’s understanding of the interface and improves navigation.

Similarity:

Designers use the principle of similarity to indicate that items share a common function or belong to the same category. This can involve using similar colors, shapes, or icons for related elements, making it easier for users to identify patterns and make intuitive decisions.

Closure:

Closure is applied to create visually complete elements. For instance, progress bars are designed to fill up gradually as a task is completed, providing users with a sense of closure and progress feedback.

Continuity:

Designers leverage continuity to guide users through processes or flows. Using smooth and continuous transitions between interface states or providing clear visual paths can help users understand how to navigate or interact with a product.

Figure-Ground:

This principle is used to emphasize important elements on a screen. Designers highlight the main content or call-to-action buttons by creating a clear contrast between them and the background, ensuring users can easily identify the focal points.

Symmetry and Balance:

Creating balanced and symmetrical layouts helps maintain a sense of order and visual harmony, contributing to a more pleasing user experience. This can be seen in the arrangement of elements on a webpage or in the design of app interfaces.

Simplicity and Prägnanz:

he principle of simplicity encourages designers to keep interfaces clean, straightforward, and free from unnecessary complexity. Striving for simplicity aligns with the concept of Prägnanz, where users should easily grasp the essential information without cognitive overload.

Gestalt Laws in Interaction Design:

Beyond visual design, Gestalt psychology principles also apply to interaction design. For instance, when users complete a form, feedback should be immediate and informative, adhering to the principle of proximity (closeness in time) and closure (completion of a task).

Gestalt psychology principles, when integrated into UX design, enable designers to craft interfaces that align with how users naturally perceive and process information, resulting in more intuitive and user-friendly experiences. This leads to more efficient, enjoyable, and user-centered digital experiences, ultimately enhancing user satisfaction and engagement with a product or service.

Gestalt Psychology in Motivation & Productivity

For decades, motivation and cognitive psychology has had a layer of separation. We’ve kept distance between what drives us vs what we think, goal, and work towards — often assuming they come from separate places.

Cognitive science, though, primarily focuses on understanding how the mind processes information, including topics such as perception, memory, problem-solving, and decision-making. It seeks to uncover the underlying cognitive processes that drive human thinking and behavior.

Read More: Techniques to Motivate Your Team for Better Performance

In contrast, motivation delves into the reasons and mechanisms that initiate, direct, and sustain human actions and choices. While cognitive science explores the “how” of mental processes, motivation explores the “why” by investigating factors like desires, goals, incentives, and the role of emotions in driving behavior.

Motivation can significantly influence cognitive processes, shaping how individuals approach and engage with tasks or problems, thereby highlighting the intricate relationship between cognitive science and motivation in understanding human behavior. All of these things will impact productivity.

What do Gestalt psychology principles have to do with Leantime?

Hold on while I lean into my nerd mode here for a moment.

The traditional look at productivity and motivation has spent many recent years operating under the assumption that the dollar was enough to motivate people to successful levels of productivity.

I remember being at an event, early in our business development, discussing employee motivation with someone who stopped by our booth. He chuckled at me and said, quite simply, “My employees will be motivated if I take their checks away.” A bit surprised, I asked if he had done that before. He admitted that he had and it corrected the situation.

Why was this so impacting? Because…

Point 1: The human work experience is not linear

When we think of motivation in its simplest form, we tend to think A + B = C and that our intrinsic nature functions in a linear manner. Paycheck + Person = Productivity. Return to office + team = Productivity.

While a linear approach is useful and provides a common direction, the reality is that, similar to gestalt theory, all the many parts are what equals the human perception.

In the image earlier, did you see the faces or the elephant? Simply a black and white outline? The brain engages in never ending perceptual groupings. We take in information continuously and do not consciously process all of it. These perceptual groupings can then be applied as a holistic approach to work.

The parts cannot be explained without the understanding of the whole

There are entities where the behavior of the whole cannot be derived from its individual elements nor from the way these elements fit together; rather the opposite is true: the properties of any of the parts are determined by the intrinsic laws of the whole.

Max Wertheimer (1925), Lecture at the KANT Society on 17 December, 1924.

Just in case this quote was skimmed on first read, I’m bringing it back here.

A paycheck is one part. Productivity is one part (albeit an output). Motivation is one part. Purpose is one part. Feeling included is one part.

Enjoying what you do is one part. Knowing that you matter is one part. Contributing to impact is one part. Building amazing things is one part.

Understanding how your work impacts the goal is one part.

The way we think, the way we move, the way we see, the way others see us, the work we do, the company we work for, the culture the company builds, the situation at home.

These all contribute to the “whole” of the human experience at work.

Unfortunately, when it comes to managing the work and managing communication around work, we’re still thinking A + B = C. It’s: “I’ve got you. I’ve got a task. Now where’s the output? “

Our ability to stay motivated has to go beyond the dangling carrot of dollars.

Point 2: The need to complete the picture

Motives are always a kind of striving for some form of completion – Allport 1937They say that a person is more likely to remember an uncompleted task, or even an interrupted one, over a task they completed. It’s called the Zeigarnik effect. In the original study, participants were able to recall the unfinished tasks 90% more often than the completed ones.

Why? Well, along with the pattern trends of gestalt theory, the brain strives to see things moved into completion. It’s in the lack of completion that haunt us, drive us to finish the picture, close the circle.

I’ve never seen this more true than in fields of creativity; whether that is in research, engineering, software development, product, art, design, marketing.

By nature, we are creators. We see problems and we see fixes. Society runs, grows, and changes because of our natural drive for modern development.

What happens, then, when we get into job roles where we don’t see completion?

What happens when we’re not privy to the purpose and vision for the “pieces” that we’re creating?

What happens when it’s unclear how the part 1 that I’m working on — works with part 3 and 4?

Work becomes a pain point

Work becomes a point of irritation. That nagging thing that you can never close the circle on.

Years ago, we could see the outcome of our work when things were rooted in manufacturing. We build with our hands, our head, and put ourselves into the work we were doing and maybe we’d even get to see someone interacting with that product outside of work.

But a true testament to how there is more required? Even in manufacturing, unions were born.

I’ve recently spoken to engineer after engineer and other team members that said they didn’t understand what they were working towards or what the goal was. They didn’t know what the end result should look like — just what this one piece should be like. The pieces never equal their sums — and if you’re building a product, it is the sum that creates user experience.

The people on your team have the ability to define the requirements, to understand where the holes are going to be, to know the customers, to share in the vision. A business will make better decisions when they are included in the journey.

Point 3: Strategy, vision, and goals are often elusive

There is no requirement that everyone should be in on every detail of a company’s strategy but the point here is that there is value in giving the right amount of information to the team members so they can simply focus and complete the picture; knowing they are all working in the same direction.

The statistics are grim. Projects fail left and right. Strategic initiatives fall short. Employees don’t know what they’re working for. Employer loyalty is in the drain. Even middle managers think about quitting their jobs on the daily.

In our drive for making the pieces work, we’ve been leaving out the big picture.

Leantime exists to connect work + purpose together

Other project management, work management, business management systems or whatever other fancy words are being used to describe the same thing these days… focus on the functional elements of work.

They look at A + B = C and then they rely on groups of very busy humans to be able to orchestrate, coordinate, and clearly communicate the relevant information at the right time and in a way that is clear to each very different person on a team.

What does this result in? Only 28% of middle managers and executives are able to express even 3 of a company’s business strategies. The others? None at all.

The tools are accommodating the natural tendency to action. By nature, we are action focused. We look for solutions. We see a lion coming at us, we run — we don’t plan our escape.

But again, the individual pieces do not speak for the sum of the whole picture.

Leantime is the intentional effort to connect the pieces together while increasing intrinsic motivation and boosting dopamine.. in a clear, easy to communicate, way.

Leaning into gestalt, cognitive psychology, neuroscience and behavioral science

Beyond just asking ourselves, “How do we show case work?”

We ask ourselves, “How do people naturally work?”

Then another step back. “How do we also make this work accessible to people from all walks of life?”

The process of work is a whole picture effort. It touches the mind, the body, the emotions and separating the experience — it creates an incomplete picture — where, in a prolonged environment, it creates added stress, conflict, frustration, and makes it harder to work. Decreasing engagement and decreasing productivity.

Using AI to augment the human work experience

One of the future ways that Leantime addresses this is by looking at the emotional side of how we perceive tasks. Resource management in the work environment is heavily weighted by effort and priority rather than by who has both the skills and who also enjoys the work.

Why are we handing out tasks that people hate when it could be completed more quickly by someone who enjoys that challenge?

Because we have spent the last decades focusing on the pieces, the outputs, and not the picture.

This is where Leantime adopts artificial intelligence (AI) in order to make the best recommendations to a user on which tasks they should start with so that they enjoy the process — and to avoid procrastination driven by task disdain.

It’s the human experience of working.

In Summary: Running a business requires more than task management

We’ve explored how the human brain perceives information, groups key elements, and processes visual stimuli. This understanding of human sensation has implications for more complex systems. Our brain and social behavior are influenced by how we perceive the working world around us.

As we build and explore the features within Leantime and the impact that our humanistic element has on the way we work, we consider these principles as a foundation to to our own vision. We recognize that it’s the big picture that drives the ultimate outcomes and we’re always looking for the best way to include that in the way we manage work.

Sarris, V. (2020). Introduction to Max Wertheimer:Productive Thinking . In: Sarris, V. (eds) Max Wertheimer Productive Thinking. Classic Texts in the Sciences. Birkhäuser, Cham. View Resource