The Goldilocks Dilemma: Finding ‘Just Right’ Productivity when You have a Disability

I have pain every day and the reality is that very few work, and life activities, can wait for pain. Life keeps on going and many of us have to make hard choices on the level of life we can handle that day. This pain and other conditions have reshaped how I interact with the world and how I manage my productivity, and often, I find what I need doesn’t align with traditional working models. And it’s not that I can’t work — it’s that the way the world says I have to work is disabling.

The prescription that changed my life came from a rheumatologist very early in my journey, “Be active, but not too active.”

Since that advice, the amount of work hasn’t decreased. It’s grown: I was diagnosed with ADHD, my daughter as Autistic with ADHD, and I’m working on a PhD in Industrial & Organization Psychology while we bootstrap (largely self fund) Leantime.

My doctor’s advice played a big role in my realization: Living with disabilities is the ultimate Goldilocks scenario.

Productivity advice isn’t made for Goldilocks. It’s meant for hustle culture and for corporate profitability. We see it in early manufacturing when companies fought having to set reasonable hours for work. The Fair Labor Standards Act was what gave us a 44 hour work week in 1938 (later 40 hours in 1940). Before enacted, manufacturers were working their employees as much as 16 hours a day.

It’s taken me awhile to learn where my Goldilocks zone is but it’s forced me to fundamentally rethink what productivity means when you have invisible disabilities, neurodivergence, or any other condition that doesn’t fit the traditional model.

Productivity has to change and the things most important in finding that “just right” productivity lives in balancing energy, strategic impact, and your motivations.

Understanding Disability and Neurodivergence: Beyond the Medical Model

Before diving into productivity strategies, it’s important to understand what we mean by “disability,” particularly invisible disabilities like ADHD, Autism, and chronic health conditions.

Is ADHD a disability? According to the Americans with Disabilities Act, yes—conditions that substantially limit major life activities qualify as disabilities, and ADHD certainly impacts executive functioning, attention, and self-regulation.

However, there are two fundamentally different ways to view disability: the medical model and the social model. The medical model frames disability as a deficit, a problem within the person that needs to be “fixed” or “overcome.” It becomes an inconvenience to the system rather than something the system can benefit from. As a nurse, I’ve seen the lack of empathy in this model and it fails to recognize the natural diversity of humanity.

In contrast, the social model—which is our position here—sees disability as a mismatch between an individual’s needs and their environment. The problem isn’t the person; it’s the environment’s failure to accommodate diverse ways of being. Just as we need different types of trees, flowers, and ecosystems in nature, our differences bring essential perspectives and strengths to our communities and workplaces.

I’m not a flaw or a break in the matrix — I have a different operating system with particular features, capabilities and strengths. This perspective shift is crucial for developing effective personalized productivity approaches.

The Hidden Impact of Chronic Stress on Productivity

Trying to optimize for someone else’s definition of productivity creates stress. The research on chronic stress reveals just how significantly it impacts our cognitive function and productivity.

A study by Liu et al. found that chronically stressed individuals showed “significantly slower task response and lower accuracy” in attention-related tasks. The researchers discovered that under chronic stress, our brains struggle to “assign attention to effective information” and have “difficulty in maintaining alerting.” Most concerning, chronically stressed individuals needed to “allocate more cognitive resources to deal with conflict tasks,” meaning simple decisions become increasingly draining.

Living with these effects is exhausting. When I’m managing high stress levels, my ability to focus dissolves. Tasks that should be simple—like deciding what to work on next or switching between activities—suddenly require immense mental effort. And the research confirms this isn’t just perception; it’s measurable through neurological indicators like changes in ERP (Event-Related Potential) components of brain activity.

For neurodivergent individuals already navigating executive function challenges, chronic stress makes it worse. The cognitive resources needed to compensate to fit in a system not tolerant of us — are the very same resources depleted by persistent stress.

This creates a vicious cycle where demands increase stress, stress decreases performance, and decreased performance leads to more stress.

Without intentional structures to reduce cognitive load and decision fatigue, those of us with invisible disabilities can quickly spiral into overwhelm — and overwhelm, to burnout.

The scattered, constantly-switching, notification-driven work style that has become standard in many workplaces is actively harmful to those managing chronic stress or neurodivergence.

The Burnout Crisis: Unmanaged Workplace Stress

The progression from chronic workplace stress to full-blown burnout is particularly dangerous for neurodivergent individuals and those with invisible disabilities. Burnout—characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy—is now recognized by the World Health Organization as an occupational phenomenon resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.”

For those of us navigating ADHD, autism, or chronic health conditions, the path to burnout is often accelerated. The constant compensation required to function in unaccessible work environments depletes our energy reserves faster, creating a perfect storm for burnout syndrome.

Research on employee burnout shows alarming statistics: up to 77% of professionals have experienced workplace burnout, with disabled and neurodivergent workers being particularly vulnerable. 1 in 5 neurodivergent individuals have experienced harassment at work, including resulting from not making proper accommodations and 77% of HR professionals have had zero training on neurodiverent needs.

The economic impact of burnout is staggering, with increased absenteeism, higher turnover rates, and reduced productivity costing organizations billions annually. In fact, burned out workers are 3x more likely to look for another job. More importantly, the human cost is devastating—relationships suffer, physical health deteriorates, and mental health conditions like depression and anxiety often develop or worsen.

The traditional burnout prevention advice—”just practice self-care” or “learn to say no”—places the responsibility on individuals rather than addressing systemic workplace issues. True burnout prevention requires structural workplace accommodations that account for neurodiversity and energy limitations.

The Cost of Unclear Focus in the Workplace

Without clear focus areas and defined outcomes, both organizations and individuals pay a steep price.

Research shows that chronic stress interferes specifically with our ability to maintain alertness and handle conflicting information—precisely the skills needed to navigate ambiguous work environments.

The cognitive burden of constantly having to determine what’s important is especially challenging for those of us with ADHD, where the executive function struggles are already in motion. Our brains work overtime trying to create structure where none exists, leading to mental exhaustion before we’ve even started actual work.

In organizational terms, this translates to reduced productivity, increased errors, and higher turnover. It results in spending valuable energy trying to figure out what matters instead of delivering actual work products. The physical and mental toll accumulates over time, often resulting in burnout, health issues, and disability leaves that could have been prevented with clearer work structures.

Clear, concrete, and communicated expectations at work can and should be considered an accommodation for everyone.

This is why the Focus-Outcome-Task approach is so transformative (more below), especially for those of us motivated by tangible impact. By establishing clear categories of work and explicit desired outcomes, it dramatically reduces the cognitive load associated with ambiguity.

Reframing Productivity With A Disability

Most productivity systems were designed by and for consistent energy and motivation. In fact, the standard work week was built with the assumption that there would be a “Homemaker” who handled everything else.

Work environments continue to assume you can power through tasks with enough discipline and that time is your primary constraint. We particularly see this in university environments where student accommodations are typically more “time” for projects.

But when you’re disabled or neurodivergent, energy—not time—is your most precious resource in achieving workplace productivity.

Photo by Riccardo Annandale on Unsplash

The traditional productivity approach says: “Here are 24 hours. How much can you fit in?”

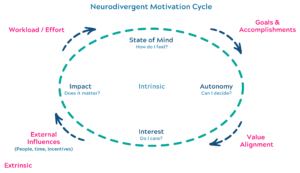

The neurodivergent approach asks: “Here’s your limited energy. How can you create the most impact?”

This shift isn’t admitting defeat; it’s recognizing reality.

My worth isn’t measured by how many tasks I complete, but by what I accomplish with the energy available to me.

It’s hard to unlearn but moving from a deficit-based view (“I should be able to do more”) to a strength-based approach (“How can I optimize my unique capabilities?”) has been liberating when managing ADHD and other invisible disabilities.

Understanding Your Energy Landscape: The Circadian Rhythm

The first step in my productivity journey was mapping my energy patterns. My energy fluctuates dramatically based on my health, medication timing, and even hormonal cycles.

I started tracking when my thinking was clearest, when my creativity peaked, and when my body needed rest. This wasn’t just about identifying “morning person” or “night owl” tendencies—it was about recognizing that my brain processes different types of tasks better under different conditions.

For example, I discovered that:

- My analytical thinking is strongest in the early morning

- Creative work flows best in the late afternoon

- Administrative tasks are manageable during energy dips (most of the time)

- Some days are “deep work” days, while others are only suitable for light tasks

Understanding these patterns allows me to work with my biology rather than against it. Now, instead of feeling guilty — I recognize that energy management isn’t the same as being inconsistent or procrastinating. It’s now something that I can leverage as a natural rhythm.

Add Systems to Your Workflow: A Energy Productivity Foundation

With ADHD, willpower is an unreliable resource. No amount of “trying harder” will overcome neurological differences in executive function. This is why systems are essential.

A system is an external structure that reduces cognitive load and decision fatigue. For me, this means:

- Creating environmental cues that trigger behaviors automatically

- Establishing routines that don’t require constant decision-making

- Using implementation intentions in the form of “When X happens, I will Y”

Implementation intentions have been game-changers. Rather than saying “I’ll work on my dissertation this week” (which my ADHD brain promptly forgets), I create specific triggers: “When I finish my morning coffee, I will work on my dissertation for 25 minutes.”

These systems aren’t about forcing myself to be productive. The goal is to give my brain scaffolding to hold onto, including triggers that anchor behaviors. It’s leaning into what my brain does naturally by giving it intention.

The Focus-Outcome-Task Model: Clarifying What Matters

I’ll be the first one to admit that I’m horrible at task lists (the To Do list). When I break all my work down into lists, I end up overwhelmed by the number and then I see how the number continues to grow in demand. This has driven me to use our internally developed Focus-Outcome-Task model.

This framework works particularly well for my Impact driven mind, where I need to be able to see that I’m making smart decisions rather than jumping from activity to activity… just to spin in the hamster wheel. This three-tier approach helps me organize my work in a way that aligns to tangible outcomes — where a small collection of tasks amounts to tangible outputs and then I can break down into more nuanced activities as needed.

This also enables me to work on things that exist within that specific focus area and when things come up outside of this area, I can easily justify saying no rather than take on more.

Here’s how it works:

Focus Areas: These are the major domains of my life and work. For example:

- PhD in Industrial & Organizational Psychology

- Work as a Registered Nurse

- Building Leantime (neurodivergent productivity tool)

- Family responsibilities

Outcomes: Under each focus area, I identify specific results I need to achieve. For instance:

- Under PhD: Complete Tests and Measurements class, Develop Motivational Profile for Neurodivergents

- Under Nursing: Complete 3-4 eight-hour shifts weekly, Receive biweekly paycheck

- Under Leantime: Refine website, Define AI feature expectations

Tasks: Only after establishing focus areas and outcomes do I break down into specific actionable tasks.

Note: In our current tests, this model works best for folks who often start Big Picture and then break down into immediate tasks. There is a greater learning curve for those who start with the details and have to build up. We’re currently testing how to best approach this framework from details up.

Maximizing Impact: The Strategic Focus Approach

With limited energy, I can’t do everything—so I’ve had to learn to identify high-impact actions that create the most visible and meaningful results.

This is where we develop focus areas. When facing an overwhelming situation (like a messy house before visitors arrive), I identify one category of tasks that will create the biggest visual or functional impact. Often, this means focusing on one type of item or one area of a room, rather than trying to clean everything.

For example, if my kitchen is a disaster, I might focus solely on clearing dirty dishes. This creates a visible improvement that motivates me to continue, rather than getting overwhelmed by trying to tackle everything at once. And if I don’t have the energy to do the full project? Then I’ve still made progress by tackling the most impactful items.

The same principle applies to work projects. I ask myself: “What’s the 20% of this project that will create 80% of the value?” This allows me to direct my limited energy toward tasks with the highest return.

Create Your Own Workplace Accommodations Through Energy-Impact Analysis

One revolutionary moment in my productivity journey was realizing I was creating my own accommodations based on my energy-impact analysis.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) recognizes that people with disabilities have the right to reasonable accommodations, but the standard accommodations don’t always address the unique needs of neurodivergent individuals.

By analyzing my energy patterns and identifying high-impact tasks, I’ve been able to advocate for specific accommodations that allow me to maximize my contributions. For example:

- Flexible scheduling to work during my optimal cognitive hours

- Permission to use noise-canceling headphones to minimize sensory overload

- Breaking large projects into smaller, more manageable components

This self-advocacy approach doesn’t just benefit me—it helps organizations understand how to better support employees. When I explain my needs in terms of energy management and impact optimization, it shifts the conversation from “fixing deficits” to “enabling strengths.”

Tools and Techniques from the Leantime Toolkit

My personal struggles with productivity as a neurodivergent person led me to create Leantime. Our platform is built specifically to support the way neurodivergent brains work, where we are currently building and adapting with the community.

Unlike conventional productivity tools that often overwhelm with endless features and never-ending flexibility, Leantime provides:

- Visual organization options to reduce cognitive load

- Flexible structures that allow you to adapt to energy fluctuations (we’re building in more in depth energy management)

- Impact and interest focused prioritization tools

- AI focused on behavioral science and motivational psychology research specific to cognitive accessibility

The Future of Productivity: Cognitively Accessible and Personalized

Looking ahead, I believe the future of productivity lies at the intersection of cognitive accessibility and personalization. Traditional one-size-fits-all productivity systems are becoming obsolete as we recognize the incredible diversity of human cognition and needs.

The next generation of productivity tools—like what we’re building at Leantime—will adapt to how your unique brain actually works, not how someone else thinks it should work. These tools will leverage AI to learn your energy patterns, cognitive strengths, and work preferences to create truly personalized systems.

This future isn’t just about accommodating neurodivergent and disabled individuals—it’s about unleashing our potential. When tools match our natural thought processes, we can achieve flow states more easily and contribute our unique perspectives more effectively. The workplace accommodations we design today will evolve into personalized productivity environments that benefit everyone.

In the future, we won’t be sorting people into “normal” and “different” categories. Instead, we’ll recognize that everyone exists somewhere on multiple spectrums of cognitive patterns and our tools will have to support wherever we fall on those spectrums.

Conclusion: Sustainable Productivity IS Self-Advocacy

Redefining productivity around energy and impact isn’t just a practical strategy—it’s an act of self-advocacy and self-care for those of us with invisible disabilities. By acknowledging my limitations and leaning on my strengths, I’ve had to find a sustainable approach to workplace productivity that prevents me from burning out.

This journey has reinforced what we’re building here with Leantime: tools designed specifically for people whose brains don’t fit the societal molds. Proper workplace accommodations aren’t special treatment—they’re about creating equal opportunity to contribute for everyone.